The White Lund Explosions October 1 – 4th 1917

One hundred years ago, during World War 1, one of the biggest disasters ever to happen in north Lancashire occurred in the Parish of Heaton with Oxcliffe. Between October 1 – 4th,1917 a large munitions factory, which covered most of what we now know as the White Lund Industrial Estate, was destroyed by explosions and fire. In 1915, the British army was running out of armaments and it became clear that there would be no quick victory in the War. The Government set up the Ministry of Munitions, began an emergency programme of rapid armament production and put David Lloyd George (the Welsh Wizard) in charge. The Ministry of Munitions quickly commissioned the conversion or construction of a large number of munitions factories of different types across the country.

One hundred years ago, during World War 1, one of the biggest disasters ever to happen in north Lancashire occurred in the Parish of Heaton with Oxcliffe. Between October 1 – 4th,1917 a large munitions factory, which covered most of what we now know as the White Lund Industrial Estate, was destroyed by explosions and fire. In 1915, the British army was running out of armaments and it became clear that there would be no quick victory in the War. The Government set up the Ministry of Munitions, began an emergency programme of rapid armament production and put David Lloyd George (the Welsh Wizard) in charge. The Ministry of Munitions quickly commissioned the conversion or construction of a large number of munitions factories of different types across the country.

Vickers of Barrow was commissioned to construct National Filling Factory 13 at White Lund in which empty shell cases would be filled with explosive. Building began in November 1915. Output from the factory started seven months later in June 1916. The site covered 260 acres and consisted of approximately 150 buildings linked by an internal railway. For speedy construction, most of the buildings were one storey and made of wood with felt roofs obviously susceptible to fire. The shells at White Lund were filled with amatol, a mixture of ammonium nitrate and TNT; the mix was melted down to be poured into the shells. 3 million shells were filled in National Filling Factory 13 during the War.

Another munitions factory was opened in 1915 in Lancaster on the Caton Road a National Projectile Factory. This received and finished shell casings rough-made in Barrow. They were then sent on to White Lund (by railway) for filling with explosive.

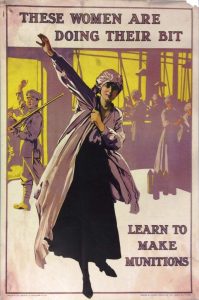

By September 1917 there were 4621 employees at White Lund, of whom 64% were women, often young women. The workers came from all over Northern England and lived in hostels and lodgings throughout the district. The Factory worked seven days a week, 24 hours a day. It was dangerous work. Coroner records show that in 1917 there were worker deaths on a monthly basis: for the men from accidents and for women normally from TNT poisoning. Toxic TNT powder transferred from the hand to the mouth. Officially there were stringent health and safety regulations and a Munitions court was established in Lancaster in the attempt to enforce them. Smoking and possession of tobacco and cigarettes were regular offences and could be punished very severely by prison sentences with hard labour. Yet there was little difficulty in recruiting workers. Munitions work was relatively well-paid for both men and women and promoted to potential recruits as the chance to do their bit on the Home Front as soldiers gave their lives on the War Front.

By September 1917 there were 4621 employees at White Lund, of whom 64% were women, often young women. The workers came from all over Northern England and lived in hostels and lodgings throughout the district. The Factory worked seven days a week, 24 hours a day. It was dangerous work. Coroner records show that in 1917 there were worker deaths on a monthly basis: for the men from accidents and for women normally from TNT poisoning. Toxic TNT powder transferred from the hand to the mouth. Officially there were stringent health and safety regulations and a Munitions court was established in Lancaster in the attempt to enforce them. Smoking and possession of tobacco and cigarettes were regular offences and could be punished very severely by prison sentences with hard labour. Yet there was little difficulty in recruiting workers. Munitions work was relatively well-paid for both men and women and promoted to potential recruits as the chance to do their bit on the Home Front as soldiers gave their lives on the War Front.

But this White Lund factory was an accident waiting to happen. At about 10.30 pm on the evening of October 1 1917 there was a massive explosion in one of the melt plants. Thereafter, explosions continued in rapid sequence throughout the night until 6 am and then intermittently until 3pm the following afternoon. The biggest explosion occurred about 3 a.m. First there was a sort of demonical hissing and leaping blue flame, and then the reverberations of an enormous explosion which destroyed any plate glass or windows still surviving for miles around.

Ferocious fires spread from building to building, setting off loaded shells where it found them. At the time of the fire 22,000 filled shells were waiting to be sent to France. Some explosions could be heard as far away as Burnley and Rossendale and the glare in the sky from the fires was reported to be seen from the outskirts of Liverpool. The Factory fire brigade was, of course, unable to contain the fires and fire crews from all over the region were called in. The last fires were not put out until the early morning of October 4th.

When the alarm was raised most of the workers were in the canteen on their supper break. This probably saved many lives although some workers were injured in the rush to escape the site. It was amazing that only ten people – all men – were killed in the disaster. Most of them died while actually fighting fires. Five were firefighters, five were munitions workers. Several bodies were not discovered until all the fires were out. There were, of course, many injuries at White Lund caused by falling debris, shrapnel, burns, crowd panic and confusion. In the neighbourhood, injury and illness was caused to local residents by falling masonry, shattered glass, shrapnel, accidents in the streets and inadequate clothing and exposure on a cold night.

Anne Harrington, aged 11 at the time of the explosion, recalled that we [lived] about a mile from the factory the girls who worked nights at the factory were running terror-stricken past our house. My mother tried to persuade some of them to come into the house but they were much too scared. She went on, perhaps less credibly, that some of them ran right round Morecambe Bay and as far as Kendal. John Taylor of Heysham, who was 6 years old at the time, recalled the arrival at his home that evening of a young woman munitions worker who lodged with them. She was all muddied up. She crawled through the ditches to get clear.

Anne Harrington, aged 11 at the time of the explosion, recalled that we [lived] about a mile from the factory the girls who worked nights at the factory were running terror-stricken past our house. My mother tried to persuade some of them to come into the house but they were much too scared. She went on, perhaps less credibly, that some of them ran right round Morecambe Bay and as far as Kendal. John Taylor of Heysham, who was 6 years old at the time, recalled the arrival at his home that evening of a young woman munitions worker who lodged with them. She was all muddied up. She crawled through the ditches to get clear.

Panic also seized local inhabitants in Lancaster and Morecambe throughout the night as shells screamed overhead and houses were shaken by repeated explosions. Anne Harrington described how, in flimsy night-clothes, she and her family made our way towards the seafront. Every time there was a flare we knew there would be an explosion and we dropped to the ground covering our heads with our arms [In Morecambe] as the blast shattered shop window glass flew all around us. Many people were badly cut. The family struggled to the Stone Jetty because it reached out into the Bay. We came at last to the old stone pier there were hundreds of people sitting there. Fortunately, the shells, as they exploded, just cleared us, whistled over our heads and fell into the sea. It was absolutely terrifying. It was a night of full moon, almost as light as day and the shells were visible as they passed over us, huge things they were about 6 feet long.

There was much local anxiety and speculation about the cause of the explosions and fires. There were immediate rumours of a German invasion or sabotage by the newly-formed IRA. Some people claimed that there had been a German Zeppelin attack (this was just about feasible – in 1918 a Zeppelin bombed Wigan thinking it was Sheffield). However, the most likely cause was worker carelessness with cigarettes despite the strict rules and heavy penalties to deter smoking.

Between October 1917 and January 1919, official censorship prevented details of the White Lund Explosion and its effects on Lancaster, Morecambe and district appearing in newspapers. It was announced simply that an explosion had taken place in a factory in the north of England. John Taylor remembered that his father was at the Front in France at the time and heard about the explosions three days after they occurred. Men going back from leave spread the word: they knew about it in the trenches before a lot of people in England recalled Taylor. Nevertheless, in June 1918 publicity was given to citations and awards made for heroism during the disaster and this, necessarily, made more information available nationally. Firemen, policemen, munitions workers, nurses and civilians were decorated with OBEs, Edward medals (forerunner of the George Cross) and other awards. More than 30 awards were made.

By the morning of the 4th October 1917 the factory was almost entirely devastated. Virtually all of the 150 buildings of the Factory were destroyed with the exception of a few on the western perimeter of the site which were partly brick and the one notable exception of the (electricity) Power House which remains today alongside the current cycle and pedestrian path (which itself is the site of the Lancaster-Leeds railway which serviced White Lund).

Most Factory workers were soon paid off or transferred to another part of the country. Two weeks later two more men were killed when a shell exploded during the clearing of debris. Yet such was the perceived war-time need that National Filling Factory 13 was soon rebuilt with the use of more brick in construction. From the summer of 1918 the re-opened Factory was engaged in meeting the increase in demand for HS (mustard gas) shells.

After the Armistice in November 1918, shell production ceased and the Factory went into reverse gear – part of it was used for emptying unused shells. This led to another disastrous, although more contained, explosion on January 14 1920 when nine men in one building were killed, most probably through the negligence of one of them. National Filling Factory 13 closed soon after and the site slowly evolved into the Industrial Estate which thrives today.

Text by Dr Keith Percy